This essay is meant to provide historical context for the dataset and maps hosted on Hokkaistory.ca, while also setting the stage for two printed essays that carry the story of information in the creation of Hokkaido into the twentieth century. This story, the dataset, and these essays altogether comprise my dissertation, submitted to fulfill the requirements for a PhD in history.

Introduction

In the waning days of the summer of 1856 a precocious youth named Ekashihashui from the Ainu kotan (village) of Abuta on the North Eastern coast of Funkawan Bay approached the cartographer, travel writer, and Bakufu agent Matsuura Takeshirō. Ekashihashui styled his hair in a samurai top-knot, wore Japanese style clothing, and introduced himself with the Japanese name of Ichisuke. He spoke Japanese fluently and demonstrated a mastery of written Japanese, claiming to have learned it in only a year by studying Japanese maps and books. Ekashiahushui begged Matsuura to take him to Edo because he had ceased to be Ainu, and was now Wajin, the term Japanese used to self-identify when they traveled and lived in the islands North of Honshu. Impressed by the boy's sincerity and ability, Matsuura used his status to obtain the necessary travel permits from the Bakufu's local headquarters in Hakodate, and brought Ichisuke with him to sam oro-un kur, as the territories of the Japanese were called in the Ainu language.[1] This well known, but little examined episode of cultural boundary crossing on the Northern periphery of early modern Japan illustrates the complexities hidden behind the existing narratives of Japanese exploitation and Ainu dependence leading inevitably to the 'destruction' of the Ainu as a distinct ethnicity, and the establishment of a virulently nationalist strain of modern settler colonialism.[2]

An examination of the way information moved through this colonial space on Japan's Northern periphery can bring new trophes to bear on this complex area of investigation.[3] Information here is meant as a very special kind of human artifact whose role is to bind together three separate classes of entity to make a unique and powerful kind of tool.[4] Human information begins when materials are physically manipulated to conform to shared genres, tropes, and lexicons of established discursive forms, which in turn represent, model and imagine the embodied human relationships that power social, political and economic structures and organize collective human endeavours.[5] Information though, is not just a material medium, discursive content, or intersubjective relationship, but the intangible thread with which individual human beings are able to tie together entities from each of these domains to extend and magnify their innate physical and cognitive abilities through collaborative action.[6] Imagine the basic unit of information in the form of a fine vibrating tendril of attention and activity by a single human being. Each individual is the source of countless of these tiny tendrils, as moment by moment they shift and re-focus their attention and behaviour on messages embedded in the objects around them. These tendrils represent the expenditure of energy by individuals to create and maintain connections to other communicating subjects. Though these tendrils manifest independently in physical, discursive, and social environments, they are fixed in space and time by their origins and reception by conscious human beings.

On a broad, systemic level the tendrils gather and resonate in patterns that link individuals collectively to persistent (material, discursive and structural) features of information ecosystems, but also reveal vectors where human energy and attention is directed in specific paths.[7] With sufficient leverage, it is possible to systematically manipulate the topography of such an ecosystem to cultivate consistent patterns of subjectivity that will reliably produce certain behaviours and relationships on individual and collective scales.[8] From 1604 to 1868 the Tokugawa Bakufu, or military government of Japan based in Edo, attempted to lock together the three components of information in a 'trusted system' that standardized technologies, discourses and identities in order to impose control on the landscape and its population.[9] This system reached the shores of Ainu Moshir, the homeland of the Ainu, where it encountered an indigenous system of local communication.

In the account of the interaction between Matsuura and Ekashihashui there is evidence of coordinated attention to the meeting point of these two systems of information (See Appendix). One of these systems was centred around an evolving concept of Japanese proto-nationalism that depended, in large part, upon the construction of a universal and precise geographical lexicon tied to a physical, metaphorical and social centre. In the summer of 1856 this system was exerting increasing pressure and influence on the more distributed indigenous system based on local geographic lexicons tied to survival technologies, oral literary and ritual traditions, and communal structures of authority and status. At first, for their own reasons, both Matsuura and Ekashihashui struggle to acquire the materials and skills required to open the possibility of discourse across the physical, discursive and social boundaries that separated them. Then they frame their messages in forms that match a shifting mental map of the knowledge and ability of their interlocutor, and finally come to an understanding of their relative locations within a complex constellation of overlapping and open-ended zones of status, identity and property that link them to common and exclusive collectivities.[10] Matsuura recorded the conversation thus:

I replied that I would take him when the Bakufu removed the prohibition. But his justified response was, 'No, these prohibitions are from the past are they not? Nowadays that kind of thing has little force. I may have been an Ainu then, but now I have become a naturalized (帰化) wajin. If you say it is not possible for a former Ainu to become the same as wajin, then why did I study so hard to learn this new language, and why did I get this hairstyle in this severely cold place?' [11]

While Matsuura is concerned with the feudal power structures that provide his livelihood and make him useful to the Ainu youth, Ekashihashui is banking on the efficacy of the material and technical trappings of these power structures to carry him across invisible boundaries of colonial space. Each man apprehends different patterns in the ceaseless din of information around them, and then selects, mimics, appropriates and transforms materials, discourse and social roles in order to reshape and reposition themselves in relation to each other, and to larger patterns. These activities, through thin tendrils of attention to matter, discourse, or status, make minuscule, but cumulative alterations to the larger ecosystem, thus generating historical change. But, because of systemic and personal reasons, neither man can see the pattern in exactly the same way as the other. What is clear to one is noise to the other. That Ekashihashui was ultimately successful in becoming Ichisuke is evidence that, even as late as the 1850s, there was considerable noise in the Bakufu trusted system's application in Ainu Moshir, and that within this space Ekashihashui could construct a plausible Japanese identity without abandoning his local indigenous identity.

Ekashihashui was successful despite the fact that an integral process of the Bakufu trusted system was that it actively accumulated and standardized information in a systematic attempt to reduce noise, or undesirable communications. It teased its own patterns out of collected tendrils of attention and effort, amplifying and broadcasting them with the aid of powerfully coordinated nodes of concentrated human thought and activity. Cartography is one of the Bakufu's pattern making tools that had a powerful set of affordances.

It [the map] is a tool of spatial classification that uses selective generic signs to reduce complex landscapes to order and pattern. It is also a tool of cultural construction that uses versatile signs to mark the invisible as well as the visible, the social as well as the physical character of space. And in these markings, the map naturalizes artificial constructions by conflating human and physical geography. Cartography operates, in sum, according to a logic unlike other media. To make a map to choose to make a map rather than a landscape drawing you must embrace that logic.[12]

The encounter between Ekashihashui and Matsuura is part of this pattern, one of a long series of investigations and interventions by Matsuura and men like him that have cumulatively raised the resolution of projections of the Northern Territories as a Japanese place with layers of discourse. This accelerated accumulation of knowledge and the power that accompanied it has been well documented theoretically as a modern global phenomena, as well as in its material, discursive and political connections to Japan and its northern periphery.[13] Exploring the boundaries of this system can go a long way towards contextualizing the origins of the Eki-tei System Stops and the county's and provinces of Hokkaido drawn in 1869 that form the core of Hokkaistory's dataset. The maps and documents reanimated here were tools in this process of raising the resolution of Japanese visions of this territory.

Still, as powerful as cartography is in capturing and organizing disparate local knowledges into universal patterns, its existence, and rise to near invisible ubiquity, does not preclude the existence of other patterns embedded within the wide and deep range of what was filtered out as 'noise' in the evolving network from which the Japanese nation-state emerged. Ekashihashui, for example, in addition to his reproduction of Japanese forms of communication, lived within an enchanted world where he was inextricably linked through ties of kinship and mutual obligation to spiritual entities or Kamui who intelligently embodied aspects of what we today call the natural world. The system that articulated these intensely local relationships had no higher authority then Ekashihashui's neighbours and family members in Abuta, but were interoperable with similar systems distributed through a vast territory known to them as Ainu Moshir, or land of the Ainu. Its primary medium was an ancient oral tradition of epic literature, as well as incantations and prayers known colloquially as Yukar. Within the social structure of the village, this body of information afforded the knowledge and practice of survival technologies and overlaid the landscape with a complex geography anchored in descriptive and utilitarian Ainu language place names.[14] While recent work has highlighted the complexity and sophistication of the Ainu information ecosystem, and shows how much global and Japanese cartographic projects depended upon it, exploring the relationship between pattern and noise[15] in an evolving ecosystem of geographical information can reveal how even though Japanese maps of Ezo-chi became steadily more accurate and precise over this period, they still depended upon Ainu geographical knowledge to gain access to the land and extract the data they required.[16]

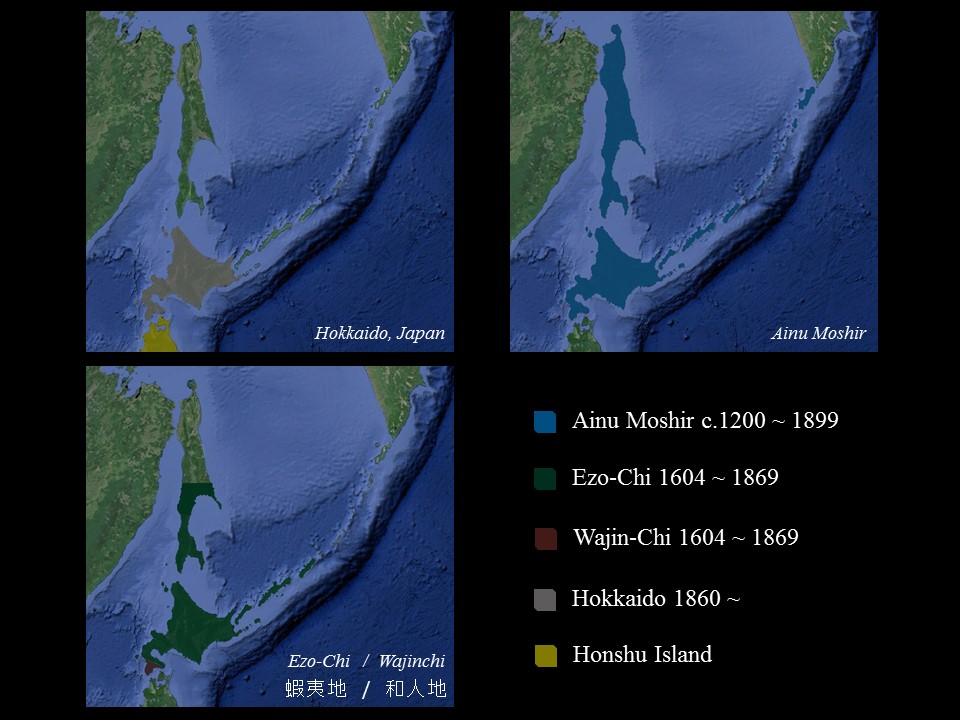

Ainu Moshir through Japanese eyes, Maps created by Joel Legassie, using Google Earth base map.

One of the principal reasons for the prevalence of noise in the Bakufu's attempts to articulate and control subject positions on its Northern periphery was a complex and shifting geographical lexicon used to inscribe the landscape into the information ecosystem. For about 1,400 years there has been a place called Ainu Moshir that included the islands of Hokkaido and Sagahlien, as well as the Kurile Chain of Islands. Ainu Moshir was inhabited and embodied by peoples who lived throughout these territories and spoke the Ainu language, lived in similar village and clan groups, and shared a common oral literature, and material culture. Some ancestors of the Ainu lived throughout northern Honshu, the island immediately south of Hokkaido, so this territory could be, and often is considered much larger.[17] From about 1600 the territory called Ainu Moshir was divided on Japanese maps into Wajin-chi (or Land of Japanese), controlled by the Japanese Matsumae warlord, a vassal of the Tokugawa Shogun, and Ezo-chi (Land of Northern Barbarians), a vaguely defined stateless territory that encompassed everything North of Wajin-chi.[18] While the cartographic distinction between wa (和) and e (蝦) cut a neat line through the landscape, it made for a dangerously narrow interface between the Bakufu trusted system, and ways of life in Ainu Moshir. Ezo-chi was penetrated and enveloped by competing articulations of Japanese subjectivities that emerged from different locations within the Bakufu's trusted system, but the Bakufu consistently failed to conjure the material resources, political vocabulary and social infrastructure required to harmonize these voices into a coherent Japanese geography of the North. In other words, the Japanese language names applied to the landscape from 1600 to 1869 provided a loosely structured framework for the organization of collective Japanese activity around the extraction of wealth from Ezo-chi. However, in its local and immediate contexts this activity was enabled by an intricate network of Ainu language proper names derived from a different taxonomic logic centred on the embodied reality of Ainu Moshir co-existing with a parallel spiritual world, known as Kamui Moshir, but also knowingly within the shifting boundaries of Wajin-chi, Ezo-chi, and Japan.

Establishing the Bakufu Trusted System in Ezo / Wajin-chi

As a way of visualizing how patterns from one system can exist in the noise of another, while also thinking about how maps carry information, imagine a hypothetical real-time map of information flows in Wajin-chi and Ezo-chi in the early 1600s. Individual tendrils of communication would concentrate in thick red lines connecting the Matsumae castle town of Fukuyama with Edo and ports in Northern Honshu. Other, finer red lines emerge from Fukuyama and other centres in Wajin-chi and Southern Ezo to enter coastal kotan throughout Ainu Moshir. These red lines indicate paths of information used by the coalescing Japanese trusted system. At this point, it is predominately commercial information, encoded in prices agreed upon for various trade goods, and materialized in the volume and mass of the goods themselves. Red lines would also follow Bakufu orders and regulations, official reports, visits and gifts from the Matsumae Daimyo and his retainers, a small trickle of published gazetteers, maps and private journals, as well as a large body of informal and orally transmitted tales, jokes, instructions and dialogues spoken in the Japanese language, would also flow southward. Surrounding and encompassing these red lines though is a constellation of green hued capillary-like and wavering strands emanating from inland and coastal kotan throughout the territory, reaching into the interior, concentrating in thick nodes at Fukuyama, and even occasionally reaching thin tendrils southwards towards Honshu, and northwards into places completely free of red. In places these thin lines, representing Ainu language exchanges of information, would come very near or even touch the red lines. There they soak up the red, but also stain the Japanese lines with a greenish tinge. At each of these points of leakage there is a person, or group of people hard at work recording and recolouring the patterns of one system so their patterns can be perceived from positions embedded within the other. While the red lines on this map appear more regular and permanent then the green because they contain written and printed materials, and flow within a sharply defined social and political hierarchy, zooming reveals that this hierarchy contains historical blockages that complicate the free flow of red into the territory.

To understand more of these blockages it will help to rewind the map's display back to the twelfth century. This will reveal the first red tinges soaking into the Northern islands when the powerful Andō clan of Northern Honshu maintained a defacto independence from the Kamakura (1185-1333) shogunate that controlled central Japan, Andō strength and wealth were based in the fortified city of Hinamoto, near present day Aomori-City, and the centre of an extensive trade network connecting peoples living north of the Tsuguru strait with expanding and consolidating Japanese territories to the south.[19] Comparisons of place names in Hokkaido and Northern Honshu, as well as archaeological evidence suggest that during this period the boundaries between Ainu and Wajin territory, and likely ethnicity, were not rigidly fixed, but were distributed in specific patterns throughout much of present day Tōhoku and Southern Ezo.[20] Still, the board outlines of a Japanese information ecosystem were laid out at this time in the form of sea and land routes connecting resource gathering sites with trading posts and consumers, a ritual discursive framework for handling trade across linguistic and structural boundaries, and subject positions that allowed individuals to represent groups defined within the discourse surrounding trade. Ainu speaking peoples forged many of these transportation routes as resource gatherers harvesting the rich natural resources within Ainu Moshir, but also as independent travelling entrepreneurs embodying an important link in an interregional flow of information and goods stretching from the Kamchatka peninsula through the Kurile Island chain, into the Asian interior through the Amur River Basin and Shakhalin Island, and south through the Japanese archipelago and beyond.[21] They linked to others at home and abroad through a series of rituals, part of an ancient and organic East Asian tributary system that provided roles and a script enabling strangers to trade goods and information peacefully.[22] In its many variations and adaptations this mode of interaction made room for the articulation of a variety of subject positions, with connections to broader institutional or social structures. At this early stage the contrast of red and green that distinguishes indigenous from foreign information on our hypothetical map would only be visible at key sites of concentration such as Fukuyama Castle, or on the level of individual interactions, as individuals manoeuvred around distantly defined boundaries to deal with pressing local matters, but the geographical and discursive channels through which the red will later flow into the space are already visible.

In the mid-fourteenth century an Andō vassal clan, the Kakizaki established a foothold on the Southern tip of Hokkaido and attempted to monopolize the Ezo trade by encouraging the 'under the castle trade,' through which Ainu chieftains were encouraged by economic incentives and military threats to carry their trade goods to the Kakizaki Castle town at Fukuyama and participate in a ritualized trade that the Kakizaki understood as a tribute to their authority and power. However, the Kakizaki were never very successful in enforcing this monopoly, and it is unlikely that their Ainu trading partners interpreted the trade rituals in the same way. In reality the Kakizaki clan operated as one of a number of military and economic powers in Ezo, rather than a domineering force.[23] Their efforts led them into a series of bloody conflicts with regional Ainu alliances that continued throughout the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, and which resulted at one point in the destruction of all of their castles in Southern Ezo except their main stronghold at Fukuyama. However, the Kakizaki, through their connection to the Japanese State as vassels of the Andō, succeeded in establishing a discursive spatial boundary between Wajin-chi, and Ezo-chi that would overtime come to organize the structural, linguistic, cultural, and ethnic boundaries among the people who inhabited these two territories. The establishment of this boundary, and its abstraction to social identities solidified the crucial discursive plank of the Japanese trusted system with a binary trope that separated 'us,' the meaning of the 'wa' (和) in Wajin (和人), from 'uncivilized others,' a rough translation of the 'e' (蝦) in Ezo (蝦夷).[24] At this point the thin red lines emanating from Fukuyama can be seen to converge and spill together to cover over the southern portion of the Oshima Peninsula. At the same time red lines linking Fukuyama with Honshu grow thicker, while the tendrils reaching into Ezo from the sea carry more of their red hue into the kotan.

With the consolidation of power in Japan at the end of the warring states period first by Toyotomi Hideyoshi and then Tokugawa Ieyasu the Kakizaki gained legitimacy and direction for their precarious position in Southern Ezo through investiture as vassals by each of these Shoguns in 1593 and 1604 respectively. After being recognized by the Tokugawa Bakufu the Kakizaki changed their family name to Matsumae and took their place as a Daimyo, (大名), or Lord, within the Bakuhan (幕藩), the political structure based on alliances and obligations between the Shogun (Bakufu), and the lords of the domains (han). The Matsumae domain was a peculiar kind of domain. Instead of receiving a parcel of land with a specific assessed value of rice production in exchange for tax revenue, military service, and other obligations, the Matsumae were charged with the protection of the Empire's 'Northern Gate,' and in exchange were awarded a monopoly over the trade in Ezo-chi. To manage the monopoly the Matsumae Daimyo assigned 'trade fiefs' to his own samurai vassals, giving them exclusive trading rights in established trading areas, centred around one or more large kotan, but often with vaguely defined boundaries. Initially 40 trade fiefs were established, but their number was increased to 63 by the end of the Tokugawa period. Matsumae vassals were responsible for managing the trade with kotan leaders in their territory, and protecting the Matsumae domain's monopoly of trade, but they did not directly control or administer any land or people within their trade fiefs. To make this arrangement worthwhile the Matsumae began to replace the traditional ceremonies of the 'under the castle trade,' with separate rituals in each fief where samurai holders brought gifts from the Daimyo to the Ainu, and in turn received gifts on his behalf. This new practice removed the threat created by annual concentrations of Ainu in the domain capital, and limited opportunities for Ainu leaders to communicate with each other, while allowing the Matsumae and their vassels to imagine, if not realize a monopoly on sea based transport reaching almost to the resource gathering areas themselves. In 1669, with the help of troops dispatched from Northern Honshu by the Bakufu, the Matsumae defeated the last serious military offensive from Ezo-chi.[25] During and after the conflict the Matsumae denied shipping to both enemy and neutral kotan throughout Ezo-chi, forcing many to surrender completely and accept the Matsumae monopoly.

The Matsumae faced a constant financial shortage, exacerbated by the fact that the domain did not produce any agricultural goods, and so had to purchase rice on the market, the price of which which rose continuously throughout the Tokugawa era. In the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, having fallen deeply into debt the Matsumae Daimyo began to contract the management of trade fiefs to merchants. This new system, know as the Basho Contract System (場所請負制), eliminated the costs of directly administering the trade in each fief, and provided stable and guaranteed streams of income in the form of contract prices paid, and customs revenue on goods shipped from official Matsumae ports at Hakodate, Esashi and Fukuyama. The contract holders' thirst for profits led to an intensification of resource exploitation in Hokkaido, exacerbated by price gouging and the use of economic clout to push credit on Ainu trade partners at exploitative rates. By the mid-eighteenth century, especially on the West Coast of Hokkaido, the basho holders started to become proto-industrialists, employing Ainu and migrant wajin workers in the harvesting and processing of herring meal fertilizer to fuel Japan's early modern 'industrious revolution.'[26]

David Howell describes feudal collective identity and social status boundaries that expressed territoriality and collective identity, bolstered by the 'language of status' as the primary structure that, however unwieldly, held together a realm of 270 autonomous warlords in Tokugawa Japan.[27] The ordered social status groups or mibun system served to organize the geographies of identity within the core polity, while at the periphery, as in Wajin-chi and Ezo-chi, notions of civilization and barbarism defined not only political boundaries but also the boundaries of identity in relation to status and location.[28]

And so, by the late 1600s the final institutional plank in the Bakufu centred trusted system that attempted to control the flow of information on Japan's Northern periphery was in place. While our map shows thick red lines penetrating deep into Ezo-chi in consistent patterns, basho holders, the Matsumae clan, and the Bakufu were all trapped in a set of feudal and contractual relationships that ossified contradictory economic and political interests, and stifled the coordinated flow of information among Japanese actors and decision makers on the Northern periphery. Basho holders had strong incentives to limit the flow of information to and from their basho to the greatest extent possible. With less independent connections between locals and outsiders, they could more easily manipulate prices, and bring their own knowledge of the broader market to bear on local trade. The Matsumae clan's interests aligned with basho holders to the extent that higher profits for merchants meant higher basho contract prices and more customs revenue. But, they also required an operational level capacity to synthesize economic and social information from Ezo-chi that spawned a bureaucratic apparatus of record-keepers, inspectors, and tax-collectors, whose activities and plans were resisted and hampered by basho holders. Because the geographic definition of the Matsumae trade monopoly, and so their position within the Bakuhan system, required the existence of a foreign territory, 'Ezo,' inhabited by 'uncivilized others,' the Matsumae, had to manufacture and maintain sharp status and social distinctions between indigenous peoples and Japanese in order to protect that monopoly.[29] As a result in the 1670s they issued a series of regulations that attempted to fix the physical boundaries between Ainu and Japanese. They forbid both Ainu and Japanese from crossing the line between Wajin-chi and Ezo-chi, forbid Ainu from speaking or writing the Japanese language, wearing Japanese clothes or hairstyles, and from practicing agriculture of any kind. These regulations though ineffectively enforced, still closed off potential interfaces between Japanese and Ainu by forcing exchanges to occur within the established ritual frames, or beneath the level of official notice.[30] For the Bakufu strategic concerns drowned out the scramble for profits that drove the flow of information closer to the ground. Sporadic, but intense direct interventions in Ezo by the Bakufu were inspired by fears of powerful Western empires advancing from the dark zones to the North of the known world, and by mistrust of the Matsumae spawned by their undignified preoccupation with commercial activity and reluctance to provide accurate and timely information about the Northern Gate, which they were charged to defend. Our imaginary map shows how these interventions cumulatively lead to greater and more patterned inflows of red into the green space of indigenous communications networks, but closer examination shows how layers of feudal, mercantilist and proto-industrial structures blocked the flow of important strategic information, making it harder for the Bakufu to clearly see and coordinate the patterns of Japanese identity and activity on the northern periphery.'

Geography and the Bakufu Trusted System: Gyōki-zu, Fūdoki and Kuni Ezu

The Shogun sat at the very apex of hundreds of years of effort devoted to the collection and cartographic representation of massive compilations of topographical and prosopographical observation and measurement for the purposes of governing people and land. The massive and truly national scale cartographic projects commissioned at semi-regular intervals throughout the Tokugawa era are well known.[31] As are the many and fruitful exchanges of both technique and content between Japanese and Europeans that kept Tokuagawa cartographers very close to the global cutting edge. But as Mary Berry explains, this bundle of geographic information technology was not just another technology of governance in the Bakufu tool box, but was fundamental to establishing not only a universal geographical and social lexicon, but also the 'pervasive habits of mind,' that could make the abstract categories and hierarchies of the lexicon conform to a known social body living in a commonly known landscape.[32]

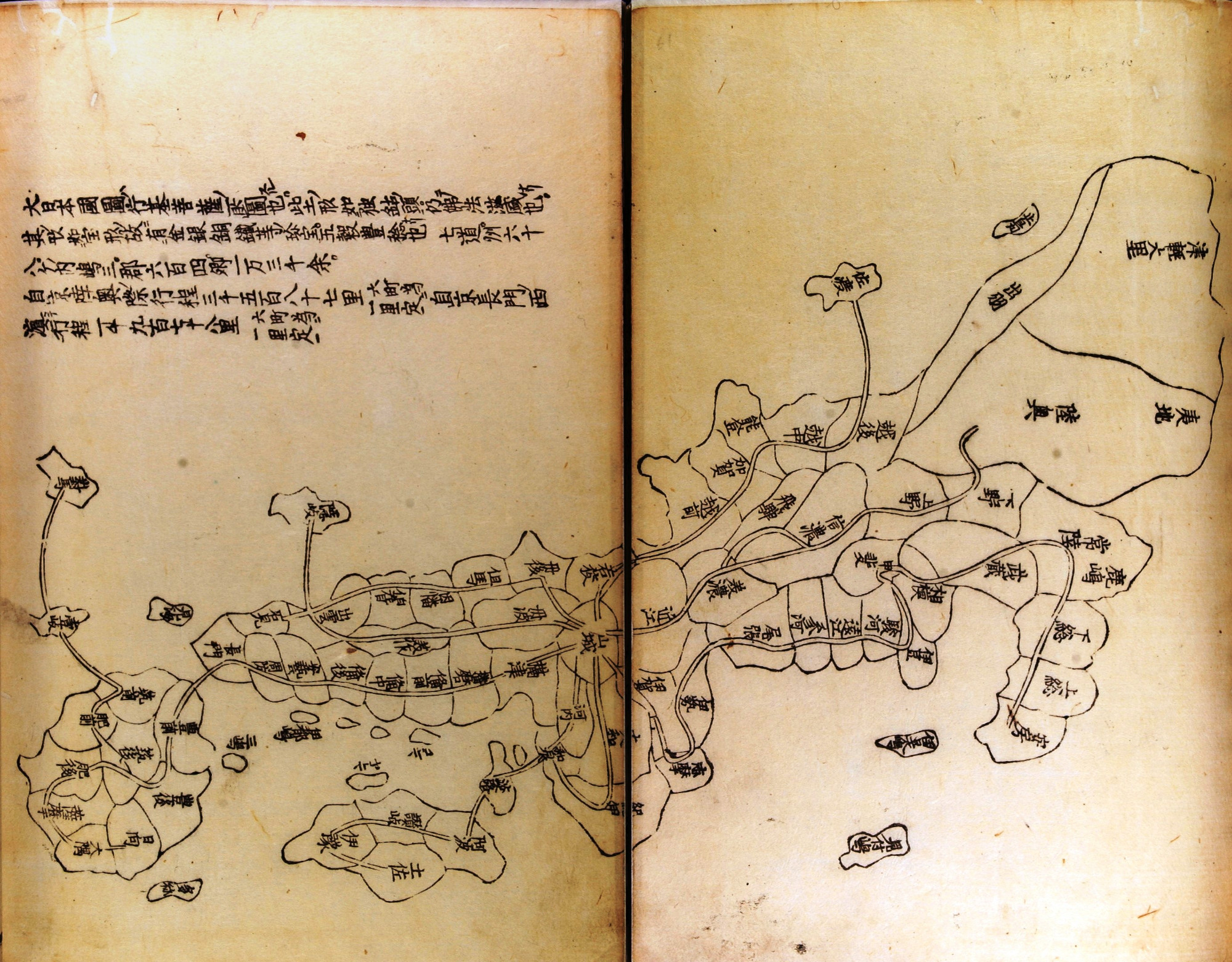

The basic geographical framework of the Tokugawa trusted system was established during the eighth century, when the gyōki-zu (行基図) genre of maps, and the gazetteer, or fūdoki (風土記) were adopted as tools of governance. Gyōki-zu are named after Gyōki (668 - 749 CE) the Buddhist monk who is reported to have made the first such map for the Emperor Shōmu (reigned 724 - 749).[33] Later, during the Heian era (794-1185) gyōki-zu typically consisted of a set of labels written in Chinese characters representing the names of provinces connected by eight snaking lines emanating from the Imperial castle at Yamashiro in Kyoto at the centre of the map. The lines represent the eight 'national' highways through which state information moved, primarily in the form of official inspectors flowing out and tribute flowing in. The relevant spatial and hierarchical relationships were communicated in the sequential arrangement of the provincial labels strung out along these lines. Later maps, such as Dai Nihon Koku no Zu often surrounded provincial labels with boundary lines that loosely represented the shape and the relative size and position of each province. In these maps the islands of Kyūshū, Shikoku, and Honshū are represented, but islands to the North of Honshū were implicitly excluded from the system of tribute and obligation that gyōki-zu maps modeled. In another edition of Dai Nihon Koku no Zu, the bounded space of each province is used to contain descriptive text about them. In addition, to the crucial provincial title, the number of counties (郡) in the province, the name of the highway it was on, and notable features such as Imperial properties, or special tributary relationships are also included.' In addition, each province contained two numbers labeled 'up' (to Yamashiro Castle) and 'down' (to the province). These numbers were derived from the number of days travel between the capital and province, but were scaled to reflect the relative value of the goods traveling in each direction. The basic extractive nature of the system modelled in gyōki-zu is apparent in the fact that 'up' values were roughly two times that of the 'down' values.[34]

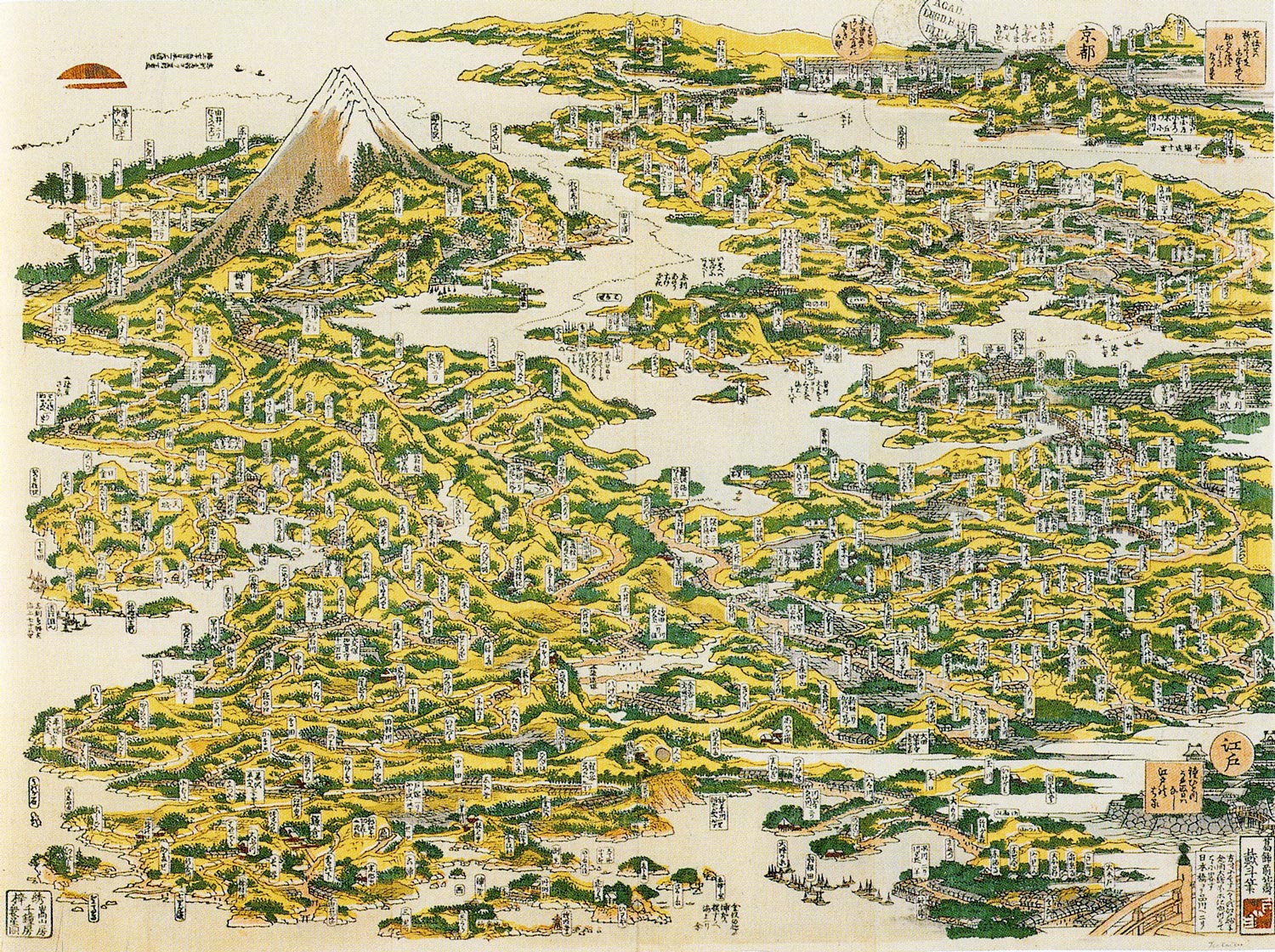

A 17th Century printed reproduction of gyōki-zu from Toin Kinkata. Shugaisho (Gathered Miscellenay). Kyoto: Murakami Kanbae, 1656.

Another early form of storing geographical information called Fūdoki pre-dated and then evolved alongside the gyōki-zu tradition. Fūdoki could represent the same hierarchical (provinces, districts, villages), and spatial (the arrangement of nodes along a radial network) framework as the gyōki-zu, but in a textual ordered list format. Trading the bounded yet whole representational space of the map with the fragmented, but infinitely extendable, list made fūdoki a container for organizing and storing the large amounts of data required to calculate the volumes of information attached to the labels on gyōki-zu maps.[35] Together the gyōki-zu and fūdoki made a given system of provinces and districts controlled by local interests into a visible and coherent system by abstracting the mental and physical labour of extracting and calculating wealth into a single visual overview of each node's relation and value to the centre. Gyōki-zu limited the descriptive detail provided by the map to a single geographically correlated data point: the position or rank of each province in the system. Viewed together from the centre of the network, these data points signified the relative value of each node in relation to the whole. In effect, the Emperor was lifted above the internal dynamics within and between provinces and was provided with a set of nodes, or axis points at which he could concentrate political and military pressure to ensure the proper flow of information (ie. tribute) moved through the defined paths of the network. Fūdoki embodied the spatial network metaphor in a textual form that afforded the expansion of the basic geographical hierarchy into a complex network of nested categories, implicitly ranked by their order of appearance in the list. These documents, such as those ordered by the Emperess Genmei in 713, provided a structured and negotiated look into the productive activities in a particular province, but without surrendering the elevated point of view of the centre.[36] Fūdoki functioned as an extendable database informing and contextualizing the overview provided by the map. They anticipated the modern application of geographically organized statistical record books that would become an indispensable tool for the modern Japanese-nation state, and which provide the data for Hokkaistory's gazetteer. Fūdoki also defined, and so limited, the boundaries of Imperial knowledge and influence in the provinces, and judging from radically different formats and styles of the fūdoki submitted by the Lords of Yamashiro and Izumo provinces, in the eighth century there was considerable local agency in choosing what to show and how to show it.[37] Still the advantage of centralizing information from most, if not all, provinces made the risks of deception, and the costs of gathering the information, acceptable. District and provincial boundaries could shift, and local powers could rise and fall, but the geography of centre and periphery visualized through gyōki-zu and populated by fūdoki provided a simple and measurable standard for comparing the potential and actual value of each province, and a foundation for the ranking, categorization and enumeration that would come to define so much Tokugawa era printed information.[38]

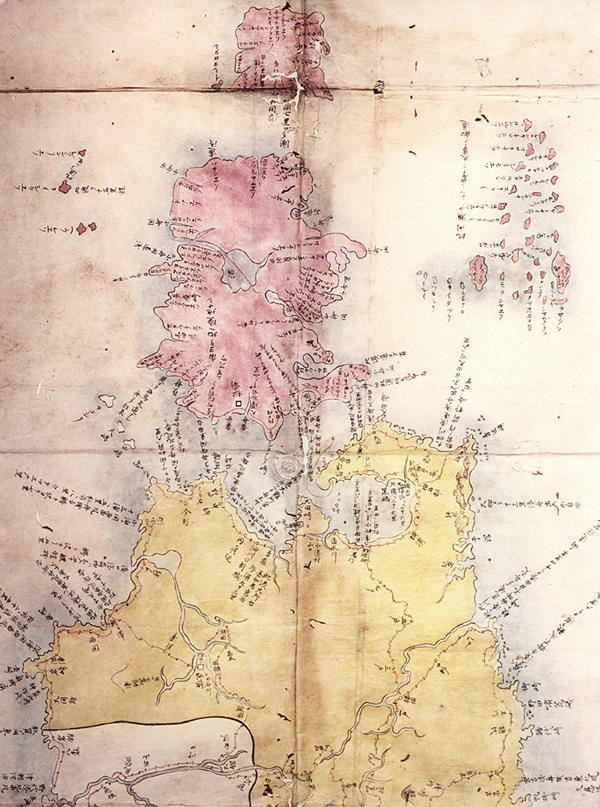

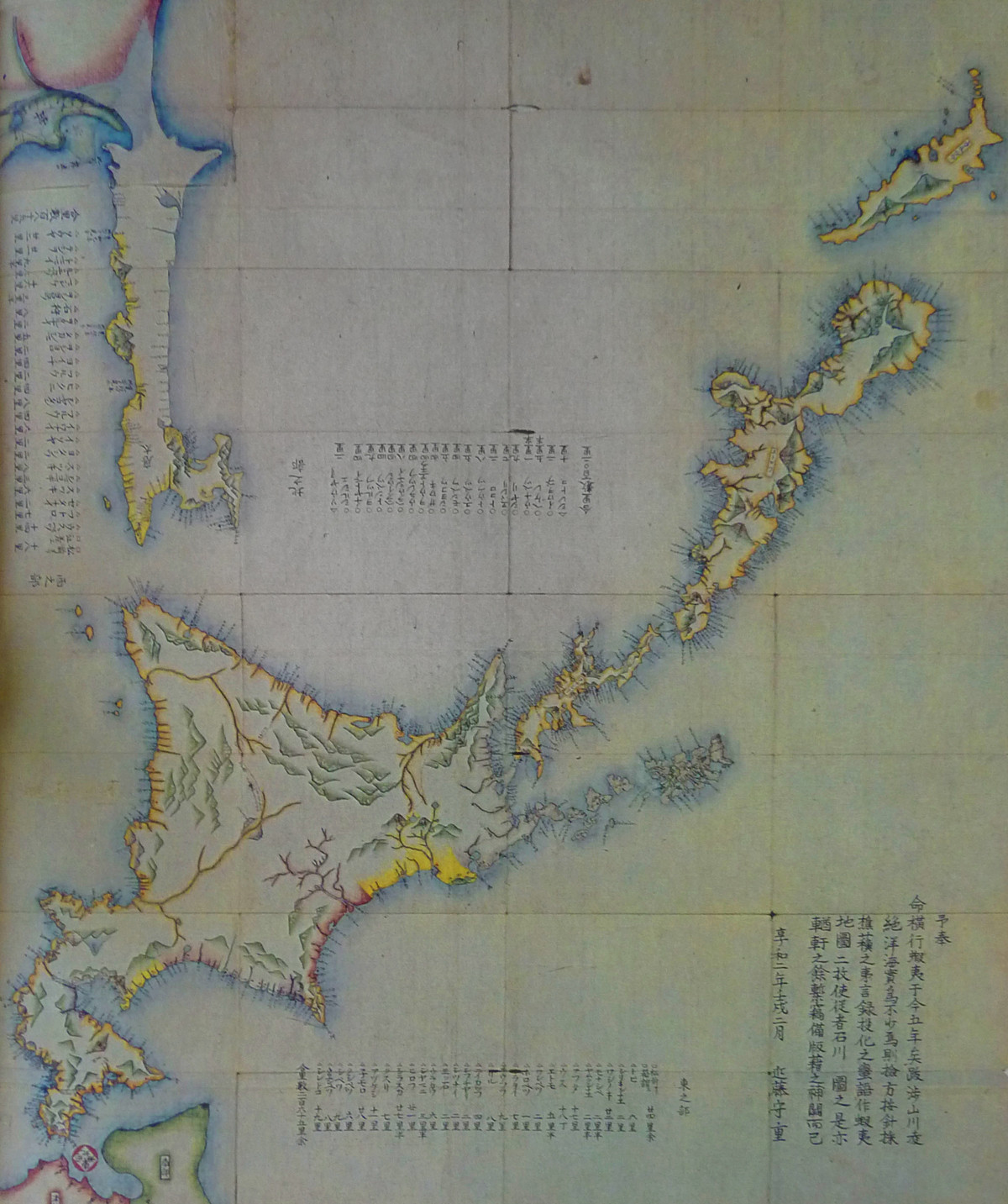

The Shohō Kuni Ezu, complied in 1644, Excerpted from Kinsei Ezu Chizu Shiryō Kenkyfūkai. Kinsei ezu chizu shiryō shūsei (Collected Maps a Pictures of the Edo Era). Vol. 15. Tōkyō Kagakushoin, 2012.

A new and more sophisticated geographical synthesis emerged from a series of Bakufu directed cadastral surveys that provided the raw materials for successively precise and detailed national maps known as Kuni Ezu (国絵図). These maps attempted to reconcile the simplicity, historical legitimacy and popular acceptance of the radial network of provinces and highways established in the gyōki-zu and fūdoki traditions with the geographical realities of the political, legal and status networks that allowed the Tokugawa Bakufu to exist. This was no mean feat. Even by the 1590s when Toyotomi Hideyoshi instituted the first in this series of cadastral surveys as a way to muster resources for his ill-fated invasion of Korea, the sixty-six classical provinces and their districts remained a key part of vernacular local geographies but no longer reflected the realities of political power and status. Instead the landscape was carved into hundreds of petty states that criss-crossed over and through provincial and district boundaries in a shifting pattern of alliances and rivalries.[39] The gazetteers and maps that projected the information gathered in the Toyotomi and later Tokugawa surveys became a powerful tool for organizing this chaos by fixing it to the classical geography of provinces and highways on one end, and to a neo-confucian articulation of an idealized social and political hierarchy manifest as the Bakuhan system on the other.[40]

The Genroku Kuni Ezu, complied in 1700, Excerpted from Kinsei Ezu Chizu Shiryō Kenkyfūkai. Kinsei ezu chizu shiryō shūsei (Collected Maps a Pictures of the Edo Era). Vol. 16. Tōkyō Kagakushoin, 2012.

In practice the cadastral surveys were initiated by orders from the shogun to each of the Daimyo for information gathered from their domains, concerning the villages, counties, provinces, and portions of provinces under their control. These orders sent thousands of low to mid-ranking samurai out into the Japanese countryside to travel highways, inspect public works, count bushels of rice, enumerate village inhabitants and to take measurements of human made and natural features within the landscape. The information generated in this process would fall under the categories of topography, ethnology, economic data (markets and production), and demographics known to us today, but it was all carefully structured within the forms of the fūdoki / gyōki-zu to provide a geographical vision organized around the classical provinces. Throughout the exercise information flowed up the hierarchy transitioning into new physical and rhetorical forms at each stage as village sketches and raw measurements were compiled into county reports, which in turn populated provincial gazetteers and maps. Finally, within the shoguns top administration, the various provincial reports and maps were converted into a single scale, national Kuni Ezu. The content of these maps evolved with each project, but their basic rhetorical strategy was to fix useful labels to the given landscape of provinces and counties. These labels located the power structure within the landscape, locating as Mary Elizabeth Berry has shown, key nodes where the social and geographical networks of power come into contact.

Within the armature of physical geography, cartographers prominently marked the castle towns of all daimyo, labeling each with the name of the town, the name and title of the daimyo ruler, and the total assessed yield of all villages within his jurisdiction. Because the productivity figures encoded both knowledge and control, mapmakers could elide the villages themselves (too numerous for inclusion) and the boundaries of the individual daimyo (too tortured for stable delineation). They created, in effect, a radiant image of power by visually conflating the castle node, the ruling lord, and the standardized figures that signified dominion over village producers and their methodically measured resources.[41]

By retaining the ancient base map of provinces and highways with an overlay of domainal authority located at specific nodes of measured production the Kuni Ezu allowed the Bakufu to refine the gyōki-zu trick of simplifying the centre-preiphery relationship to a single dimension. In this case the kokudaka (石高), or productive value of a Lord's domain, expressed in units of rice. With a stroke the Shogun could change the name of the Lord attached to a node (province), or sub-node (district, village), altering the kokudaka of their domain, and thus their status, but without disturbing the 'natural' geographic logic of the land, nor the broader apparatus of feudal relationships. While in practice the Shogun's power was constrained by political realities, the Kuni Ezu provided discursive handles with which the Shogun could address individuals within the system, and placed him in a privileged, central position in relation to all the other nodes within it. But the power of Kuni Ezu was multiplied by the fact that they actively exercised the relationships of obligation between Lord and Vassel as they were created. Social positions were embodied and landscapes materialized in the same moment they were plucked from the noise and recorded.[42]

A close up of Ezo as depicted in the Shohō Kuni Ezu, complied in 1644, Excerpted from Kinsei Ezu Chizu Shiryō Kenkyfūkai. Kinsei ezu chizu shiryō shūsei (Collected Maps a Pictures of the Edo Era). Vol. 15. Tōkyō Kagakushoin, 2012.

The Matsumae and their vassals participated along with all the others in these cadastral surveys. On the 1644 Shōhō and the 1700 Genroku Kuni Ezu Ezo-chi was depicted as a misshapen and poorly proportioned lump of islands on the edge of the map. Labels and lines concentrate around the coast of Hokkaido, and only rarely penetrate into the interior of the island, as they do frequently in other provinces.[43] The chain of tribute and obligation that extends the Shogun's gaze to Ezo-chi is very long, and so the view is obscured. As we shall see, this empty space in Ezo was filled with a strong and versatile indigenous geographical system that Ainu used to live off the land, and to interact and negotiate with Shamo who became increasingly numerous and insistent visitors and trading partners. Still the Kuni Ezu visualized the unknown as empty space and surrounded it with a net of entry points, and crucial lines of connection, however rudimentary, to the larger system.

Limitations of the Bakufu Trusted System: The Library of Public Information

Cartography was an essential tool that allowed the Tokugawa Shogun to anchor himself as the crucial apex holding together the ancient traditions of Imperial sovereignty and the realities of military and political management of the Empire, and claim to be the origin point for a restoration (chūkō, 中興) of virtue and moral order as modelled in Chinese historical literature.[44] In effect, it made individuals into interchangeable parts within the hierarchical and geographically fixed 'trusted system'. Once articulated, this system provided a powerful (and successful), discursive lever that allowed the Bakufu to direct and coordinate the skills and knowledge of millions of individuals in the extraction and accumulation of wealth from the landscape. On the assumption that morality and virtue naturally concentrated at the top of the social hierarchy, and that it must be forced upon the lower ranks, the Bakufu initially developed no mechanisms for appropriating or organizing spontaneous pattern making activities within these lower ranks. As Harootunian has argued, Tokugawa political thinking:

required the ruled to internalize the public morality which the ruler has achieved privately. No provision was made for the culmination to which the theory itself pointed: a higher stage in the development of humanity when the ruled might themselves become rulers. Instead Tokugawa Confucianists resorted to propriety and ritual as a substitute for the internalization of morality among the people.[45]

The subject positions defined within the Tokugawa Bakufu's trusted system demanded outward material compliance, but did not have the resolution to model, let alone manipulate, the activity of masses of independent and intelligent individuals if each was capable of understanding and reformulating physical, discursive and structural aspects of the trusted system from off centre vantage points inside the living system. This low resolution approach to public order and identity is apparent in the well-known political structures created by the first Tokugawa Shoguns in the early-seventeenth century when memories of the chaos of civil war still echoed across the landscape: the seclusion edicts, the ban on Christianity, the keeping of Daimyo family members as Bakufu hostages in Edo, and the hereditary monopoly on key political positions. Each of these political innovations served as a structural block to interventions in the trusted system. The basic strategy was to forbid, to immobilize or to silence those components of the system that might overwrite the carefully constructed pattern that reordered the chaos of the recent past. Instead of enforcing proper patterns onto information originating outside the centre, these structures were designed to scramble them in the hope that they would be lost in the noise. This strategy of negation eliminated specific threats that could be articulated from the point of view of the Shogun, but also eliminated possibilities of dialogue between ruler and ruled. While the Bakufu managed to keep this artificially closed system together for 260 years this strategy was ultimately an unfortunate choice for early Tokugawa rulers because, as it turns out the ruled had plenty to say and became steadily more confident and able to say it within alternative channels as the Tokugawa era wore on.

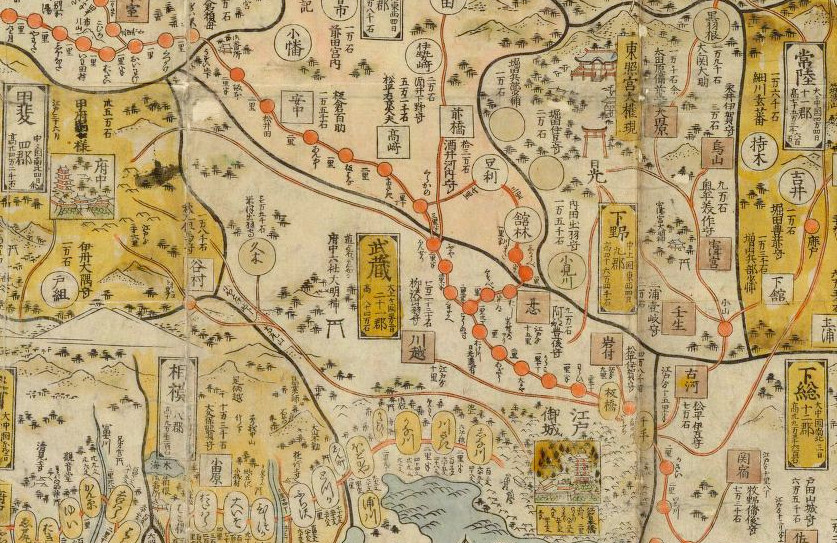

Ishikawa, Ryusen's Nihon kaisan chorikuzu zu, Edo: Sagamiya Tahe, 1694, Original held by East Asia Library, University of California, Berkeley.

In the mid-seventeenth century wood block printing technology, and the 'pervasive habits of mind' fostered by the Bakufu's massive and geographically organized information gathering program allowed millions of cash carrying, underemployed urban samurai, and increasingly prosperous urban commoners to construct what Mary Elizabeth Berry calls a 'library of public information.' This figurative library, embodied in a variety of media, formats and genres, largely occurred outside the Bakufu's discursive range, but built upon the same geographical structure, extended the tropes of enumeration and ranking developed by the cadastral surveys, and assumed the same social categories that underlaid the Bakufu trusted system.[46] But, it quickly grew to an unprecedented and (to the Bakufu) unmanageable size.

Detail of Ishikawa, Ryusen's Nihon kaisan chorikuzu zu, Edo: Sagamiya Tahe, 1694, Original held by East Asia Library, University of California, Berkeley.

By 1692, just in Kyoto, there were over one hundred publishing houses collectively carrying over 7,000 book titles covering 46 topic areas.[47] In addition maps, pamphlets, and printed artwork circulated widely in Tokugawa urban society. The fūdoki format for cataloguing and enumerating data organized in telescoping hierarchies keyed to geographical points strung on a globally radial but locally linear pattern provided a popular and commercially successful organizing principle that ran deeply through the library of public information.[48] The perennially best-selling traveller's gazetteer was perhaps the most literal application of this form. These gazetteers usually followed the route of a religious pilgrimage, though gazetteers aimed at business travellers were also published. In any case the gazetteer's author would break the trip into a series of nodes, or stops strung out along an established route of travel.

Hokusai's "Tōkaidō meisho ichiran (The Famous Places on the Tōkaidō Road in One View)," from Matthi Forrer. Hokusai Prints and Drawings. New York: Prestel, 2009.

The features of each node would be systematically and successively identified, ranked and described. Gazetteers were published as simple lists under first geographical and then thematic headings, as well as in narrative forms in which the categories and their contents were not as systematically ordered. In addition to Daimyo and their ranking officials, Imperial branch families and Noble houses, mountains, temples even actors and prostitutes were enumerated, ranked and represented in published lists and ukiuo-e prints. The tendency towards pure enumeration was parodied by Ihara Saikaku when his impassioned love story Kōshoku gonin onna is interrupted by a lengthy enumeration of the wealth bestowed upon the hero by the parents of his beloved.[49] Both Ichikawa Ryusen's privately published Nihon kaisan chorikuzu zu of 1694 and Hokusai's Tōkaidō meisho ichiran of 1818, show the extent to which the basic layers of the Bakufu system was extended and multiplied to offer a multilayered and extremely high resolution overview of the historically and politically loaded landscape of the Bakufu's realm.

The spillage of the discursive trophes and social hierarchies that defined and supported the Bakufu's cartographic information system into the expanding multi-media and multi-genre library of public information represents, on one hand, a great success as it helped to circulate a common landscape, lexicon and shared subject positions that provided the levers to manage the extraction of wealth from the people and land. On the other hand, the Bakufu had no way to limit the mutations that developed as public discourse became louder, and the 'natural' hierarchy of status boundaries that raised hereditary samurai above commoners were gradually eaten away by the material realities of an urbanized society with a commercial economy. Eventually this growing gap between assumptions about the nature of the social hierarchy that underpinned the Bakufu trusted system and the actual economic and social situation led to serious challenges to Tokugawa political legitimacy that contributed to their fall, and the establishment of the Meiji government.

Complications in Bringing the Library to Ezo

The library of public information and its most basic form, the gazetteer, arrived quite early in Ezo-chi, with the publication in 1687 of the anonymously published Shokuni annai tabisusume (Travel Guide for Various Countries), and Isama Nishitsuru's Ichimoku takarahoso (Invaluable Overview), which both contained sections on Ezo-chi[50] These gazetteer's begin their circuit, usually, at Fukuyama Castle, and proceed either East or West in a loop around Ezo-chi. Nodes were stretched out along the route at important places for the Basho trade, especially Basho Ports, where ceremonial and more mundane trade was carried out between wajin and Ainu. Each place was called by a transliteration of the oral Ainu language place name into phonetic Japanese script (katakana), and a variety of geographical, demographic and economic information was generated and reported from each 'stop' in the network. Seen from the sea, these Ezo-chi gazetteers closely resemble miniatures of the radial structure of the Bakufu trusted system just like other provincial or domainal gazetteers of the time. By 1855 the sea based lines of communication and transportation were dominated by basho contract holders and sub-contractors, but all official traffic ultimately flowed through Matsumae hands at the approved sites for export to Nai-chi, (内地) as the Japanese islands were known by wajin. On land however, the neat circuit becomes an arduous trek through a rugged and remote wilderness with great extremes in weather and great distances between nodes. While basho boundaries were defined and known, they were usually marked by the mouths of rivers, called, by Japanese phonetic transliterations of the Ainu language name for them.[51] The course of those rivers, and so the extension of basho boundaries into the interior was largely unknown, and difficult to penetrate. Difficult, physically, because of the thick blankets of six foot high sasa (笹), or bamboo grass in summer and of ice and snow in winter, but difficult discursively too, because the subject positions carried to Ezo-chi by the creators of this small sector of the library of public information did not operate in the same way that they did in Nai-chi. They were distorted by contact with another locally rooted, but versatile system that dominated subsistence, or survival technology, and in many places still, the gathering and movement of resources to basho ports.

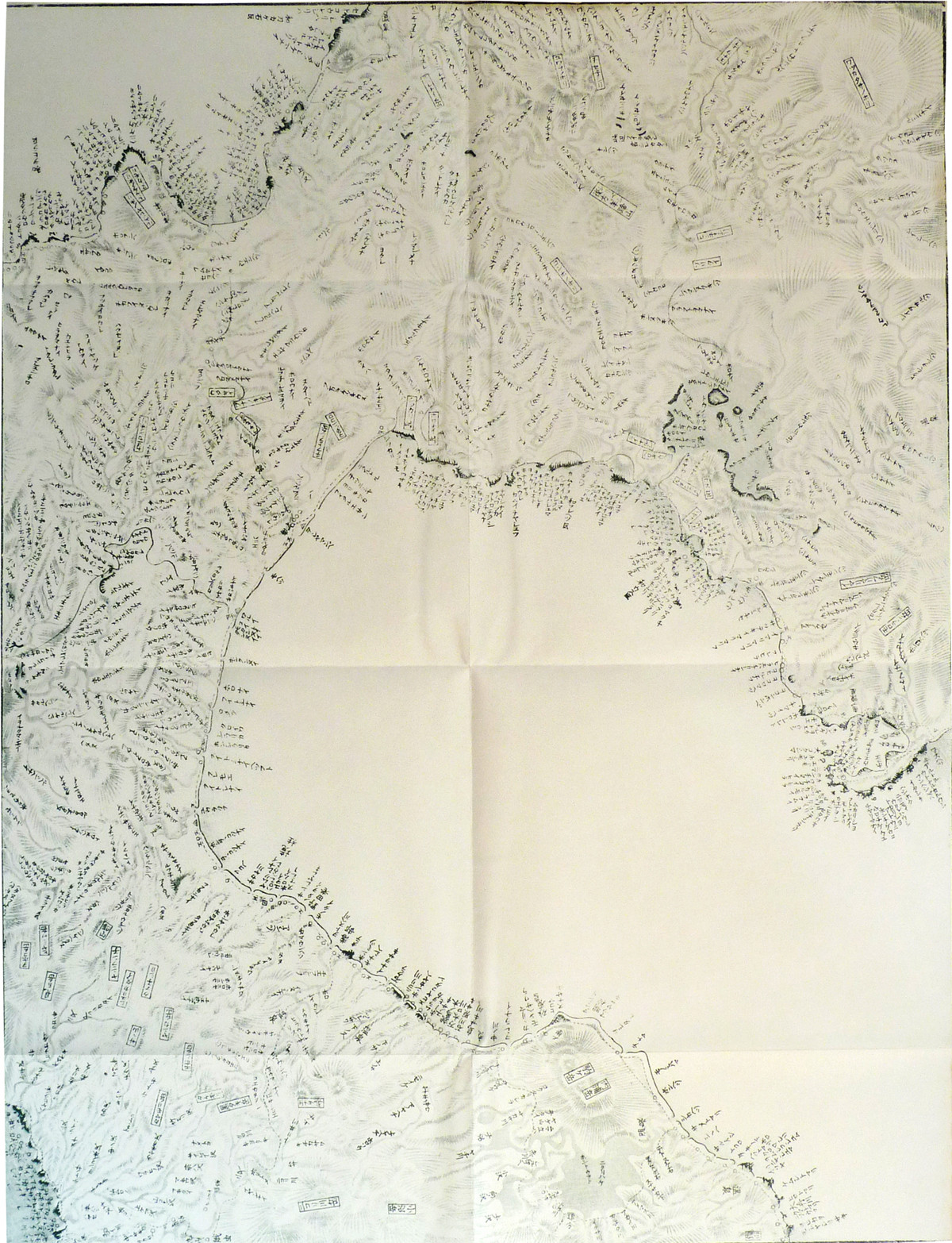

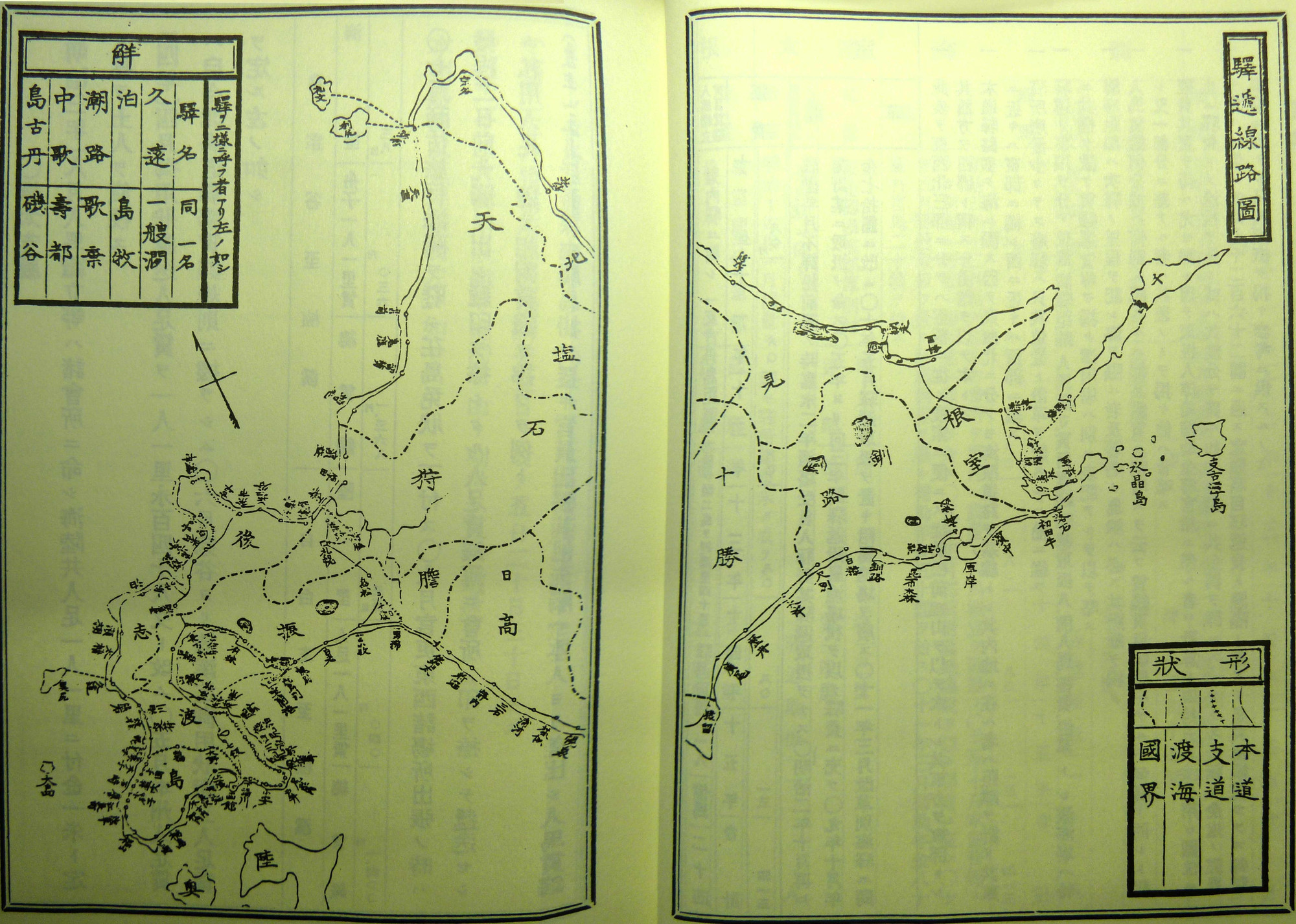

Kondō Jūzō, Ezo Chizu Shiki, 1800, reprinted in Unno, Kazutaka, Takeo Oda, Nobuo Muroga, and Hiroshi Nakamura, eds. Nihon kochizu taisei, 1972.

Simultaneously, events outside of Japan made it increasingly difficult and dangerous for the Bakufu to simply black out the insistent exterior sources of information as the consequences of European expansion and Imperialism rippled across the globe. As an external interface, Ezo-chi was a constant site of anxiety over this steadily worsening state of affairs.[52] Cartography and the investigative methods that supported it in the Kuni Ezu tradition provided a site for the exercise of these fears in 1792 when, shortly after a coordinated revolt of Ainu and Wajin fisheries workers in Kunishiri and Menashi, a Russian Naval mission under Captain Adam Laxman landed at Nemuro Nemuro requesting to open trade.[53] The Matsumae had no choice but to refer the request to the Shogun. Laxman was ignored, but his appearence set off a flurry of activity as the Shogunate tried to secure its suddenly vulnerable Northern gate. Inspectors and survey teams were dispatched, and in 1799 the Shogun took direct control of Ezo and stationed troops throughout the islands. As a result, by 1800 the Bakufu had considerably improved its cartographic knowledge of Ezo, as this map by Kondō Jūzō shows. This concentration of human attention provided a vehicle for the adaptation of Western cartographic techniques and styles to an increasingly detailed and accurate visualization of Ezo-chi that extended the Neo-Confucian geography of status encoded in the Kuni Ezu, and linked it to a global cartographic vision that was expanding in conjunction with the contagion of European Empires. In effect, fear forced the Bakufu to apprehend patterns within the external noise it was trying to jam. Once acknowledged though, these patterns echoed freely throughout the library of public information, generating novel and unpredictable patterns that complicated the techniques, categories and relationships that kept public information within the boundaries of the Bakufu trusted system. This extension of the information ecosystem contributed to the articulation of very modern sounding ideas that promised to clarify Bakufu blind spots in Ezo-chi, but that also demanded a higher resolution model of local agency.

Kaitaku (開拓), which can be translated as either 'development' or 'colonialization' the keyword of early Meiji efforts to exploit and colonize Hokkaido, was used to describe Bakufu policy and activities in Ezo during the early 1800s. But buiku (撫育), or benevolent care, another prominent trophe of Japanese state policy and popular attitudes towards the Ainu in the modern era became the watchword for Bakufu policy towards the Ainu.[54] This level of interest however proved to be unsustainable. The direct projection of power over such a distance was costly for the shogunate and troops stationed in remote posts died over brutal Northern winters. In the meantime, Napoleon began to charge across Europe, drawing European resources away from the Pacific, and the urgency of the moment passed. The Matsumae were restored in 1821, and things returned pretty much to the way they had been before. The failure of Bakufu directed kaitaku and buiku is commonly attributed to the state's inability to reach the Japanese people whose willing effort was required to complete the plan. Agricultural workers could not be moved from their home villages without reducing the kokudaka value of the domain, and so upsetting the delicate balance of status resting on these values. The other potential target, urban commoners had their own independent sources of information on Ezo-chi, and it's connections to Japan and to the wider world. Though free to relocate, why would they leave the energy and opportunity of city life for a place that was known to be a cold and lonely outpost?[55] This internal weakness is certainly part of the explanation for the Bakufu's failure, but it is equally attributable to the slippery noisiness of Ezo-chi in the Bakufu's geographical system.

Matsuura Takeshirō

Matsuura Takeshirō, from Starr, Frederick. The Old Geographer Matsuura Takeshirō. Tokyo, 1916.

By the mid-1840s Matsuura Takeshirō had established himself as one of the most energetic and reliable contributors to the Ezo-chi sections of the library of public information. As the fourth son of a rural samurai from Kitanoe Village in Ishi County, Ise Province he occupied a slightly elevated position in the Bakufu hierarchy of social status. He had access to education (his father was a pupil of Motoori Norinaga), and freedom to move throughout the country, though he had no chance of inheriting his father's modest samurai stipend. At the age of sixteen he set off on a solo journey through the Southwestern provinces of Japan, including a pilgrimage to the 88 Tengon temples of Shikoku.[56] At around this time he also took the tonsure as a buddhist priest assuming the name of Bunke, and serving at temples in Hirado near Nagasaki.[57] By the early 1840s he became deeply interested in Ezo-chi and travelled to Northern Honshu hoping to find his way to the mysterious territory. After being turned back once by Matsumae inspectors, he finally managed to smuggle himself across the Tsuguru Strait in 1843. He made this trip disguised as a merchant and travelled along with the poet Mikisaburo Rai, disguised as a doctor. The two young men spent three summers traveling throughout Ezo-chi, funding their travels by selling prints of Mikisaburo's poems made from wood blocks designed and cut by Matsuura.[58] Upon his return Matsuura published three diaries, and an anonymously published stand alone map.[59] This map was a reproduction of the coastline surveys produced by Maimiya Rinzō and Kondō Juzō, and contained only a few previously unknown place names. More significant however, was the text accompanying the map which contained a harsh polemic directed at the rapacious exploitation of the Ainu by basho contract holders and Matsumae officials.[60] This polemic echoed the reports written by Bakufu agents in the 1780s that had contributed to the Bakufu's decision to take direct control of Ezo-chi. Matsuura's skillful and timely intervention into the library of public information, expressed the fears and vulnerabilities of the Bakufu's position, making it embarrassing to them. At the same time it strengthened their case for once again taking direct control of Ezo-chi. Though this wasn't possible until American and Russian legations finally forced the Bakufu to open formal diplomatic and trade relationships with Euro-American States in 1853, Matsuura was likely marked as an asset in the Bakufu's efforts to impose its own kind of order in the North. In 1856 he returned to Ezo-chi not as a fugitive, but as a sword carrying agent of the Bakufu, tasked to collect geographical and prosographical information from the territory.

Sheet from Matsuura Takeshirō's Higashi Nishi Ezochi Yama Kawa Chiri Shuchō, from Yamada, Hidezo, and Sasaki, Toshikazu., eds. Ainugo Chimei Shiryo Shusei (Collected Research on Ainu Language Place Names). Tokyo: Sofukan, 1988.

It was during one of these trips, taken in the summers of 1856, 1857 and 1858, that Matsuura encountered Ekashihashui in Japanese dress and haircut asking to be called Ichisuke.[61] It is also during this period that Matsuura compiled his master work, the 29 sheet, 22, 000: 1 scale Higashi Nishi Ezochi Yama Kawa Chiri Shuchō (East and West Ezo Inland Survey). Again Matsuura did not make any technical cartographic advances with this map, borrowing once more from the coastline maps produced by Maimiya and Kondō. Still, he filled in much of the interior, and blanketed the coastline with nearly ten thousand Ainu language place names, transliterated into the Japanese phonetic script, Katakana. Matsuura's methods seem to have been quite simple. He travelled with a compass and a portable calligraphy set, which he used to geolocate the names of the places he visited, and to make textual and pictorial sketches. The published journals of these expeditions form a polished and selective facsimiles of his field work. Included are many perspective landscapes that show the paths and sea routes connecting the villages Matsuura visited on his journey. In many of these images scale is provided by the inclusion of two male companions equipped for travel, or actively engaged in transit. It would seem that Matsuura's work depended greatly on the cooperation and knowledge of Ainu men who understood the system of land transportation in Ezo-chi. The route that Matsuura took in his travels is significant then because it was, at least in part, determined by local Ainu intervention, but also because it is echoed in the narrative structure of his published journals, and then repeated and amplified in the Kaitakushi's attempt to codify and regulate this 'system' as a rationalized modern system.[62] Matsuura. performed a circuit which took him around the coastline of Hokkaido, beginning in Hakodate and setting off first to the East and then to the West and North. Matsuura and his audiences could have easily transposed this narrative into a spiritual figuration that sees each node on the circuit as a sacred node in a pilgrimage. It would also fit into a rigid understanding of hierarchies of distance, population and wealth that anchored both the Bakufu trusted system and the library of public information. As we will see, Matsuura was quite consciously translating and applying the old gyōki-zu model of nodes (counties or kotan) along a route that physically, discursively and institutionally links and ranks each node to the centre. I wonder if Matsuura saw another incarnation of this narrative, one shaped by the voices and actions of the people who revealed Ezo to him?

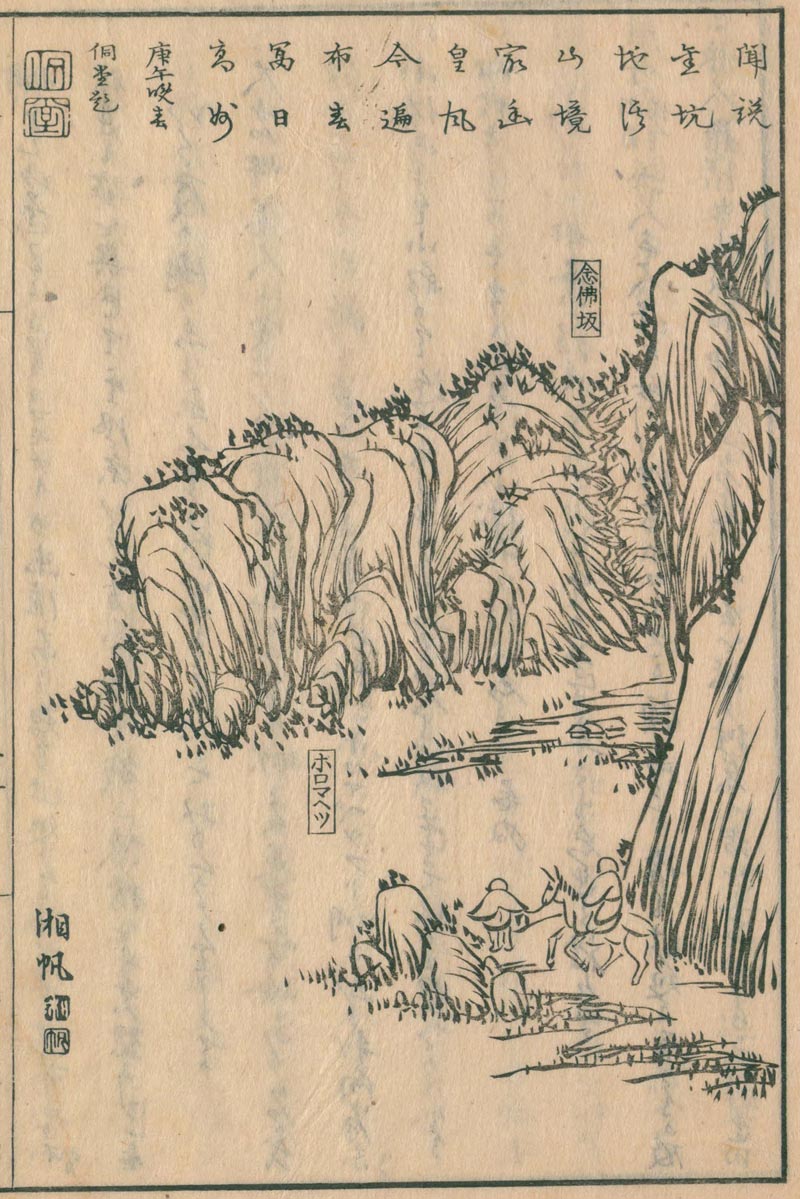

The road to Horomahetsu. A page from Matsuura Takeshirō's Eastern Ezo Journal. See Matsuura Takeshiro. Higashi Ezo Nisshi (Eastern Ezo Journal). Vol. 7. 8 vols. Edo: Kan, 1873.

A few important details of Matsuura's account of his encounter with Ekashihashui / Ichisuke reveal the possibility that he may have understood just such a narrative. As Matsuura reports Ichisuke spent all of his time in the Edo exploring the city and reporting back to the people in Abuta Kotan. Could it be that Matsuura was an unwitting pawn in a coordinated effort to gain information and knowledge of the Bakufu system of information? This would be an extremely sophisticated, even modern, use of information technology, but one that was available to the participants in the indigenous Ainu ecosystem of information, which was largely invisible to wajin visitors and residents alike.

An Indigenous Geographical Information System

Zooming out from this charged moment and looking at the imaginary map of Ainu Moshir in the summer of 1855, we can see how vigorously and steadily the red tendrils of attention and effort circulate throughout the territory, and how deeply red activity pools in certain places: Wajin-chi and its ports as before, but also at locations on the West coast where herring fishing and processing have become practically industrial. The red has begun to penetrate the interior of the main island, following the Ishikari River, and extending into the Toyohira River Estuary that will become the site of the city of Sapporo. Closer inspection reveals many interconnected rivulets of green snaking throughout the interior and pouring into coastal villages. There is a clear difference between the deeper green colours on the Eastern Coast and the Red-Green shades found on the West Coast and the Oshima Peninsula. Still closer inspection shows that the colours on these lines are not stable. Rather than a solid shade of pure green, the lines of indigenous communication are more of a shifting aoi (青い) that can manifest hues in a wide range from sky blue to sunny yellow. The lines themselves are so short lived and the hue so unpredictable that the visual metaphor of colour cannot keep up. Reluctantly perhaps, we must put away our maps and tune a new apparatus, one that can capture and amplify the tone, rhythm and pitch of the energy generated by these shifts in colour. With some careful adjustments to the new machine we begin to hear a pattern emerging from the static, very faintly at first, but swelling slowly, until finally, after prolonged fiddling with the machine: We hear music.

With some experimentation we can find an optimal frequency and begin to explore this acoustic space. We quickly find that even though our apparatus allows recording as well as playback at variable speeds, there is a set linear duration to the content in this stream that must be respected. We must spend this time in intimate attention to the pattern before we can unlock its meaning and significance. There is no immediate overview or unilateral skipping ahead as afforded by maps and texts. As we continue to explore it soon becomes distressing how much silence exists in places where history tells us resounding music should be heard, and everywhere and always there is the steady throbbing whine that is the acoustic manifestation of what appears as red on our metaphorical map. This, because nearly all these songs, in reality, come to us through Japanese language printed books and recordings, the modern mutation of the library of public information.[63] What ultimately differentiates 'green' sounds from 'red' is that they are not packaged for transmission and redistribution from a central location but instead were organized around collective efforts to sustain human life through interaction with local peoples and landscapes. In other words this music is the data accompaniment of what are often known as 'survival technologies.'[64] It represents the ways that Ainu made and used the tools and other material culture of daily life in conjunction with a geographically rooted lexicon, powerful tropes and discursive forms and a traditional social order to support subject identities that made village and household life possible, even as the coordinated rhythm of shamo activities forced constant adjustments to the tune. Here too we find the three components of a trusted system, but one that is decentralized and non-authoritarian, and unlike the relatively low-resolution Bakufu trusted system, one that is firmly rooted in the vernacular landscape.

A sketch from Matsuura Takeshiro. Higashi Ezo Nisshi (Eastern Ezo Journal). Vol. 7. 8 vols. Edo: Kan, 1873.

Ainu discursive tropes, and a closely related geographical lexicon emerged from what is usually known as the Yukar tradition of oral literature. However, Yukar is actually only one family of a rich tradition containing several genres with a great variety of local variation.[65] Twenty-seven distinct genres of oral literature have been recorded in the Horobetsu area alone.[66] Donald Philipi, a translator of over 50 works of Ainu literature, has divided the genres into four main categories: the lyrical, the epic, the dramatic, and the ritual or ceremonial. Of these the epic genres are the most developed with both prose and metered genres, and a number of narrative forms: mythic narratives dealing with the actions of Gods, heroic narratives dealing with the deeds of recurring culture hero characters, novelistic narratives of ordinary or historical people and parodic narratives.[67] The mythical and heroic epics (Kamui-yukar, oina) are generally said to have originated between the thirteenth and seventeenth centuries before the Matsemae monopoly was established. Prose narratives (uwepeker) were elaborated during the basho contract period, including a genre of narrative incorporating shamo characters and themes (shisam uwepeker). Within this vast literature, only a fraction of which is extant today, there is a vast array of characters, human and divine, and a bewildering set of inconsistent and contradictory geographical and social contexts in which the stories take place. This literature, through the medium of countless fragile and tenuous performances among small groups gathered in intimate proximity over a period of hundreds of years made available deep and complex discursive tropes for understanding and interacting with the local landscape. These tropes did not make the same distinctions between living and non-living, human and non-human, natural and supernatural that we are familiar with today. They were embodied in subsistence practices understood as communication and exchange with sentient agents in the landscape that provided or embodied the resources and materials that allowed life to continue. Important spiritual forms of this literature completed the technological circle by embodying acts of communication with these agents, as the speakers literally gave over their bodies and voices to the Kamui, who told their own stories.[68]

Yukar blended into Ainu everyday life in a variety of contexts, and fulfilled many purposes, but it is possible to describe a prototypical context for the exchange of Yukar: at a feast hosted in the home of a local family and attended by young and old from the village, as well as guests from away.[69]Weddings, funerals, births or the return of a hunting or trade party all provided opportunities for a feast. Amid the feasting Yukar reciters would come to the front and perform a piece of their own choosing, though guests often made requests of specific reciters. During the performance guests were free to break in where the reciter made a mistake or omission in the oral text. This could lead to disputes, which were mediated by the elders present at the performance. The Yukar then were structured and depended upon collaborative technical, formal and discursive interventions, and afforded a systematic and navigable body of information that is both open and distributed. That is each performance bound local, imaginary and distant geographies together with shared figurations, and embodied subject positions, but as unique and unreproducible events the particular sites at which individuals could attach themselves varied and shifted across a wide bandwidth, leaving no central origin point or repository where control of the overall system could easily be applied.

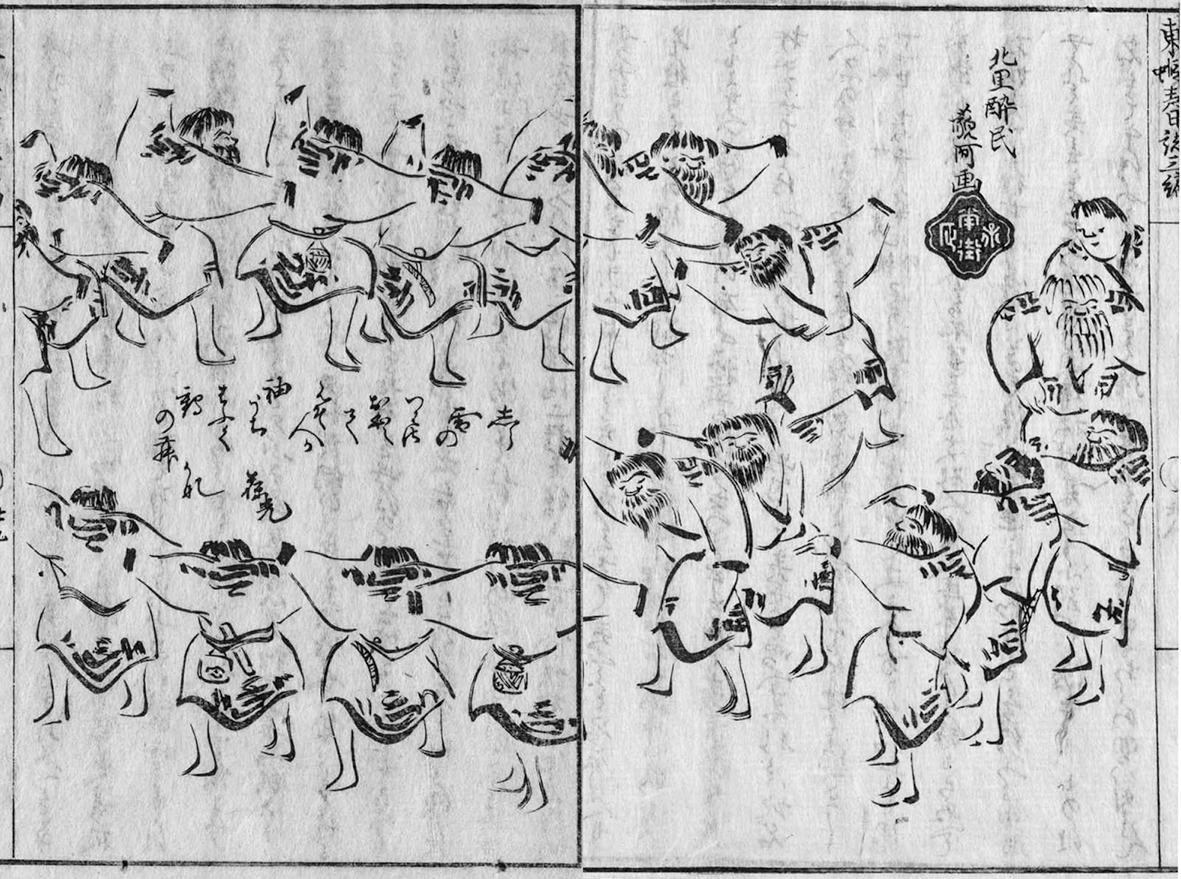

Hata Awagimaro, Scenes of daily life of Ainu people in Ezo. Painting, handscroll, 1799.

Study of the content of Yukar reveals a powerful organizing metaphor that binds together the social world of the kotan and what we would call the natural world in an eternal exchange of life force between Ainu Moshir (world of humans) and Kamui Moshir (World of Kamui). The basis of this metaphor is the immanent existence of the spiritual world as part of the local geography. Not only was the landscape populated by Kamui who manifested in the forms of plants, animals, inanimate objects and natural forces, but the physical landscape itself was divided into specific zones (iwor) where different Kamui held sway.[70] These Kamui iwor were intimately connected to the village zone (kotan iwor) where Ainu lived and gathered resources. While local geography varied, the kotan iwor generally sat between the sea, presided over by the Killer Whale God (Aty Kor Kamui) and the mountain tops, presided over by the bear God (Nupur Kor Kamui).[71] Most kotan iwor were located near a river, which made a physical and spiritual connection among the three iwor, and which fell under the influence of a local Kamui after which the river was named.[72] The human world (Ainu Moshir), overlapped with the spirit world (Kamui Moshir) at the borders of these three Kamui iwor with the kotan iwor, but there were other regions of Kamui Moshir not directly accessible from Ainu Moshir, such as an upper world (Kanna Moshir), sometimes described as heaven, and several layers of lower worlds or hells, collectively called Pokna Moshir.[73] Despite the physical proximity of Ainu and Kamui worlds their material essences were fundamentally opposed. The true form of most Kamui in their own world was identical to that of humans. They lived in village societies organized similarly to that in Ainu Moshir. However, when they crossed over into Ainu Moshir they lost their material form, forcing them to take on animal or plant form in order to physically manifest.[74] The same thing happened to humans who crossed into Kamui Moshir, though there are many stories where Ainu use magic to maintain their physical form in Kamui Moshir, so long as they don't eat or drink anything there.[75] The physical forms that Kamui took on during their visits to Ainu Moshir constituted the material means of subsistence for Ainu, and were not confined to natural phenomena, but included household tools, weapons, and luxury goods accumulated through trade.[76]

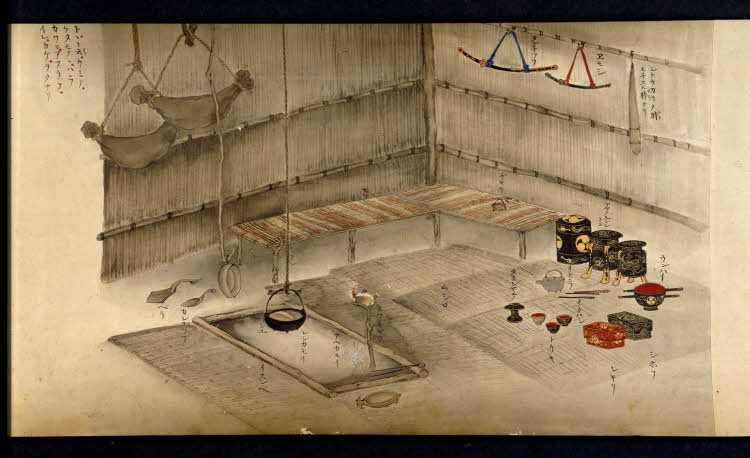

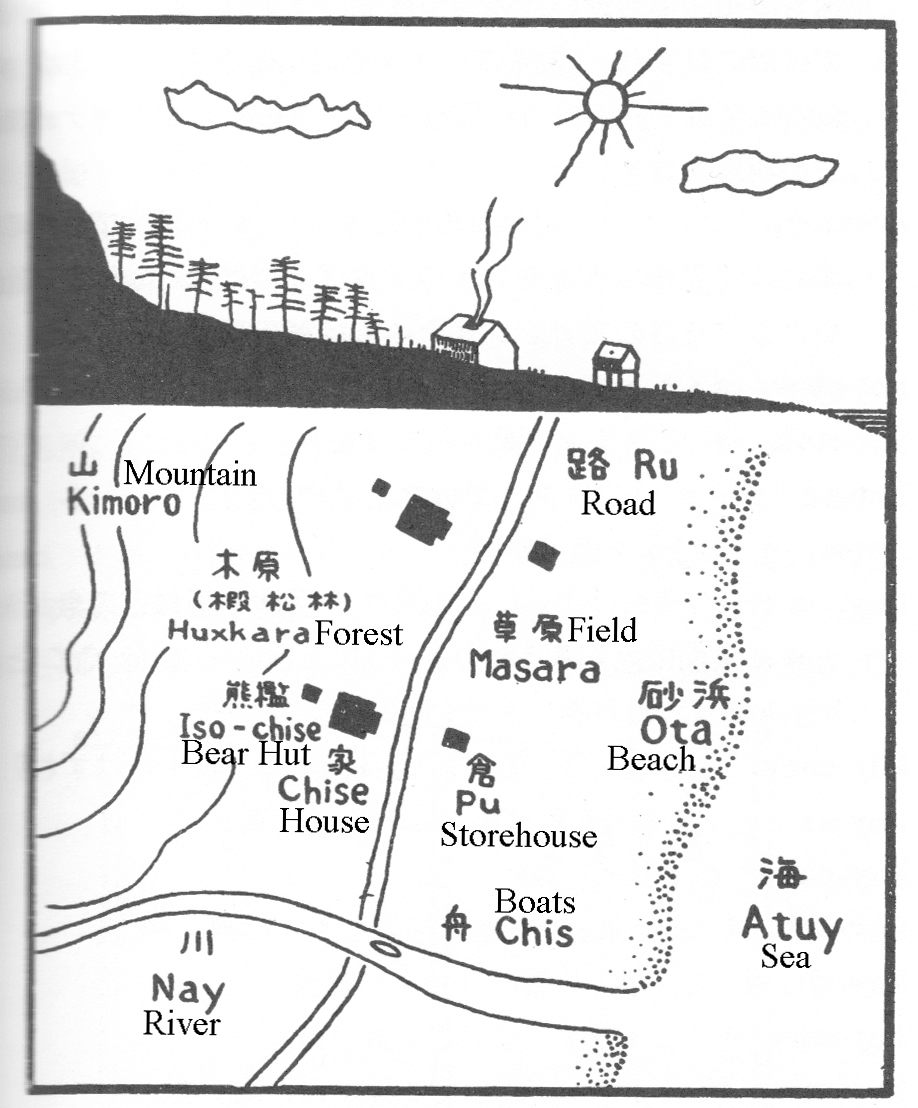

A diagram of an Iwor sketched by Chiri Mashiho. Chiri, Mashiho. Chimei Ainugo shojiten (Small Dictionary of Ainu Language used in Place Names). Tokyo: Nire Shobo, 1956., English Annotation by author.

Subsistence activities were incorporated into this multivalent landscape as acts of trade or tributary exchange among the inhabitants of the different iwor. In Ainu Moshir bodies of the different Kamui were harvested and used as tributary gifts to the Ainu. In some cases the Kamui personally embodied and carried the gift as in the case of the meat, organs and skin of the bear. In other cases the Kamui sent gifts in animal or plant form from their home in Kamui Moshir, as was the case with the salmon (Kamui Chep) sent each year by Aty Kor Kamui, and the deer sent by Yuk Kor Kamui, a powerful Kamui of the mountains. These were not one way transactions as the Ainu reciprocated with rituals and practices to fulfill their obligations to the Kamui and ensure that the exchange would continue.[77] This trade is facilitated by a number of specialized Kamui who perform important roles as intermediaries between the Ainu and Kamui worlds. The most important of these is the fire spirit, or Huchi Kamui, which translates as Grandmother Spirit. Huchi Kamui resided in the open fire pit that occupied the centre of traditional Ainu homes (chise), and transmitted the prayers and offerings of the male head of the household to the various Kamui in the spirit world.[78] The blue jay (Hashinai-uk Kamui), another female Kamui, plays an important role in transmitting male hunter's prayers and offerings to Aty Kor Kamui thus ensuring the provision of deer for the Kotan. While Ainu men liaised with female Kamui in order to penetrate Kamui Moshir with their words and material offerings, female Ainu had an equally important role in inter-world trade by serving as media through which Kamui were able to enter Ainu Moshir and exchange information and intangible gifts with the people of the Kotan. The most powerful and direct way this exchange occurred was through the recitation of Kamui Yukar and Oina, in which the female speaker was possessed by the Kamui who narrated the story. Ainu women could also be possessed by Kamui who gave them abilities to cure diseases and tell fortunes.[79] In this way, the subsistence technology was ordered around a sexual metaphor of cross-fertilization between the worlds of Ainu and Kamui that created and sustained the life force (ramat) that was the immortal essence of existence in both worlds. The circle was joined by sexual relationships between Ainu men and women producing new generations of life to fertilize and receive sustenance from the complementary life world on the other side of the spiritual divide.

An important, but often overlooked aspect of the Ainu spiritual system was that it facilitated the generation and exchange of copious amounts of information in dialogue with the natural world. This information was readily translated into practical and comprehensive knowledge that contributed directly to sustainable subsistence practices. No matter that modern science has determined that 'nature' has no intelligence and cannot communicate, the Ainu still composed and sent messages to well defined intelligent interlocutors, and were able to decode and make practical use of the feedback they received from these interlocutors to achieve the goals of the communicative process: generating and sustaining life in the iwor. While the skills of creating, preserving and transmitting the huge wealth of information stored in Ainu oral literature, and embodied in subsistence practices, are in themselves impressive and certainly proved useful in surviving within the whirlwind of information that dawned upon Ainu-Moshir in the basho contract, and bakumatsu periods, just as important is a more general awareness of the importance of the medium and form of information, as well as its content. In other words, far from being conservative and inward looking, the Ainu system of survival technology had at its core powerful tools and concepts that allowed it's practitioners to adapt to and integrate increasingly intense and insistent pressure from the Bakufu trusted system. It is a system based on a model of both fair and profitable exchange with powerful and wealthy 'outsiders.'